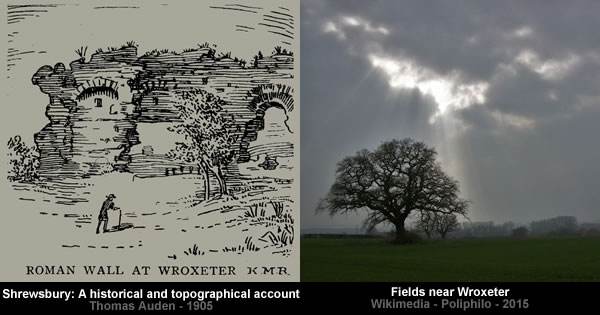

Once upon a time Wroxeter was just a sleepy Shropshire village with a Roman wall.

About five miles and a-half from Shrewsbury, close upon the banks of the river Severn, stands the little village of Wroxeter, consisting of a church, a rectory-house, and a few farm-houses and cottages.

The ground rises eastwardly from the river, the course of which is here from the north to south, and forms a gentle elevation commanding a fine view of the valley of the Severn.

Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Review – Sylvanus Urban – 1859

Then it was discovered [in 1859] that a ruined Roman city lurked beneath the fields of Wroxeter.

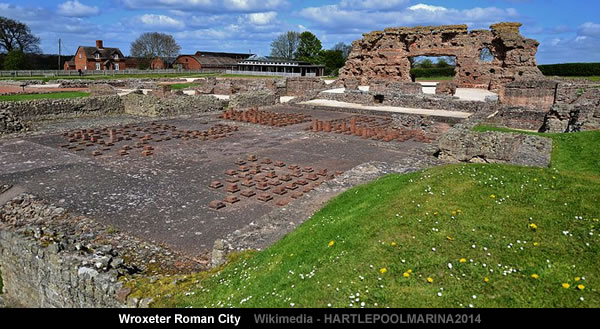

The Roman city was rediscovered in 1859 when workmen began excavating the baths complex.

This discovery wasn’t a total surprise.

Viroconium, or Uriconium, was situated at Wroxeter in Shropshire, on the north-east side of the Severn, about three miles from Shrewsbury; which is supposed to have arisen out of the ruins of that ancient city.

At Wroxeter many Roman coins have been found, and the vestiges of the walls and ramparts of Uriconium are still visible.

The history of Great Britain – Robert Henry – 1823

https://archive.org/details/historyofgreatbr02henr

But finding the “correct” name for the ruins was surprisingly challenging.

It is first mentioned in the Geography of Ptolemy, believed to have been compiled about the year 120, who enumerated it, under the name of Viroconium, as one of the two towns in the district of the Cornavii, Deva, the station of the twentieth legion, being the other, and gives as its longitude 16° 45′ and as its latitude 55° 45′ according to his mode of reckoning.

Very few relics have been found which, even by the imagination, can be carried back to this remote period of Uriconian history.

The name does not again occur during two hundred years.

The Itinerary of Antoninus, believed to have been compiled about the year 320, mentions this town twice, and gives us the means of identifying its site with certainty.

It appears first in the second iter in Britain, beginning from the borders of Scotland, and passing by way of Deva, (Chester,) Bovium, Mediolanum, Rutunium, our city which is here called Uroconium, Uxacona, and other towns, the sites of which are mostly well known, and so to London, and to Richborough.

It is the line of the great and well-known Watling Street.

In the second iter in which it occurs, and in which it is called Viroconium, as in Ptolemy, it is the termination of a road which comes from Isca (Caerleon), by way of Gobannium (Abergavenny,) Magna (Kenchester,) and Bravinium ; or in other words, it was the place at which this road joined the Watling Street.

Now there can be no doubt that the road just mentioned is the one which, called also along the border the Watling Street, proceeds northward, until it joins the other road at Wroxeter, and thus determines, without leaving room for question, the remains which are found at Wroxeter to be the ruins of Uriconium.

These are the only instances in which the name of Uriconium is mentioned in writers contemporary with its existence.

In that curious work, the compilation of the anonymous geographer of Ravenna, which is ascribed to the seventh century, but the author of which had no doubt an ancient map before his eyes, our city appears among a confused list of names of towns, under that of Utriconion Cornoninorum, an evident error for Uriconion Cornoviorum.

In another Itinerary, but one in the authenticity of which I fear we can place no trust, that given in the work De Situ Britanniae published under the name of Richard of Cirencester, this town occurs first on the Watling Street, under the name of Virioconium, and subsequently at the point of junction of the other Watling Street, under the name of Urioconio, just as in the Itinerary of Antoninus, from whom the author of this work may have copied.

But Richard does more than this, for in an earlier part of the book our city is stated, under the name of Uriconium, to have been “the mother of the other towns” of the district of the Carnabii, and to have been considered one of the largest cities in Britain.

Thus the name of our ancient town occurs during four hundred years under two different forms, Uriconium and Viroconium, and as the difference may have arisen entirely from the errors of the scribes to whom we owe the existing manuscripts in which they occur, it would be difficult to decide which is correct.

Possibly Viroconium may have been the earlier form, and it may have been gradually changed into Uriconium, and as the latter has been most commonly used by antiquaries, I shall adopt it in the present volume.

Uriconium; A Historical Account of the Ancient Roman City – Thomas Wright – 1872

https://archive.org/details/cu31924027950264

Back in the 19th century Uriconium was the “correct” name for the ruins even though this implied the city had gone south by about 3º since Ptolemy determined it was located at 55º 45′ North [sometime between 120 AD and 150 AD – depending upon source].

Coordinates: 52.670°N 2.648°W

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wroxeter

It is first mentioned in the Geography of Ptolemy, believed to have been compiled about the year 120, who enumerated it, under the name of Viroconium, as one of the two towns in the district of the Cornavii, Deva, the station of the twentieth legion, being the other, and gives as its longitude 16° 45′ and as its latitude 55° 45′ according to his mode of reckoning.

Uriconium; A Historical Account of the Ancient Roman City – Thomas Wright – 1872

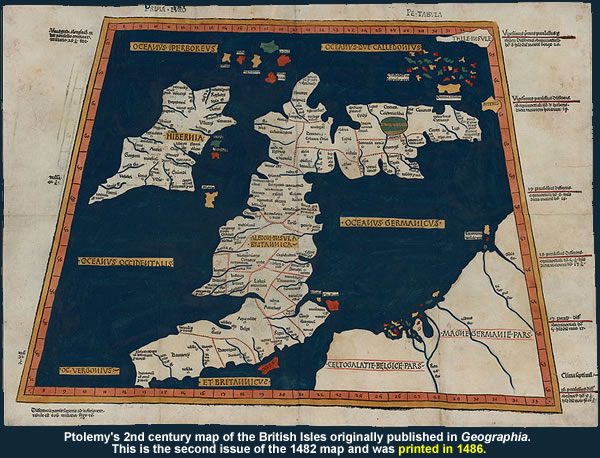

https://archive.org/details/cu31924027950264But it was Ptolemy (c. AD 90 – c. AD 168) who first used a consistent meridian for a world map in his Geographia.

Ptolemy used as his basis the “Fortunate Isles”, a group of islands in the Atlantic which are usually associated with the Canary Islands (13° to 18°W), although his maps correspond more closely to the Cape Verde islands (22° to 25° W).

The main point is to be comfortably west of the western tip of Africa (17.5° W) as negative numbers were not yet in use.

His prime meridian corresponds to 18° 40′ west of Winchester (about 20°W) today.

At this time the chief method of determining longitude was by using the reported times of lunar eclipses in different countries.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prime_meridian

The Geography, also known by its Latin names as the Geographia and the Cosmographia, is a gazetteer, an atlas, and a treatise on cartography, compiling the geographical knowledge of the 2nd-century Roman Empire.

Originally written by Ptolemy in Greek at Alexandria around AD 150, the work was a revision of a now-lost atlas by Marinus of Tyre using additional Roman and Persian gazetteers and new principles.

However, just to make life less confusing, the mainstream currently uses three “correct” names.

Viroconium or Uriconium, formally Viroconium Cornoviorum, was a Roman town, one corner of which is now occupied by Wroxeter, a small village in Shropshire, England, about 5 miles (8.0 km) east-south-east of Shrewsbury.

And when it comes to Viroconium there is plenty more confusion.

Firstly: Confusion about how exactly did Britain manage to lose its “4th-largest Roman settlement”.

At its peak, Viroconium is estimated to have been the 4th-largest Roman settlement in Britain, a civitas with a population of more than 15 000.

Secondly: Confusion about why there are so few contemporary references to Britain’s “4th-largest Roman settlement”.

It is first mentioned in the Geography of Ptolemy, believed to have been compiled about the year 120…

…

The name does not again occur during two hundred years.The Itinerary of Antoninus, believed to have been compiled about the year 320, mentions this town twice…

Uriconium; A Historical Account of the Ancient Roman City – Thomas Wright – 1872

https://archive.org/details/cu31924027950264

Thirdly: Confusion about why the only British source document that references Urioconio is a “literary forgery” that was first published in 1757.

In another Itinerary, but one in the authenticity of which I fear we can place no trust, that given in the work De Situ Britanniae published under the name of Richard of Cirencester, this town occurs first on the Watling Street, under the name of Virioconium, and subsequently at the point of junction of the other Watling Street, under the name of Urioconio, just as in the Itinerary of Antoninus, from whom the author of this work may have copied.

Uriconium; A Historical Account of the Ancient Roman City – Thomas Wright – 1872

https://archive.org/details/cu31924027950264The Description of Britain, also known by its Latin name De Situ Britanniae (“On the Situation of Britain”), was a literary forgery perpetrated by Charles Bertram on the historians of England.

It purported to be a 15th-century manuscript by the English monk Richard of Westminster, including information from a lost contemporary account of Britain by a Roman general (dux), new details of the Roman roads in Britain in the style of the Antonine Itinerary, and “an antient map” as detailed as (but improved upon) Ptolemy.

Bertram disclosed the existence of the work through his correspondence with the antiquarian William Stukeley by 1748, provided him “a copy” which was made available in London by 1749, and published it in Latin in 1757.

By this point, his Richard had become conflated with the historical Richard of Cirencester.

The text was treated as a legitimate and major source of information on Roman Britain from the 1750s through the 19th century, when it was progressively debunked by John Hodgson, Karl Wex, B.B. Woodward, and J.E.B. Mayor.

Fourthly: Confusion about how the inhabitants of Viroconium became “divided” after they “ceased to exist”.

Following the Roman withdrawal from Britain around 410, the Cornovians seem to have divided into Pengwern and Powys.

…

Viroconium may have served as the early post-Roman capital of Powys prior to its removal to Mathrafal sometime before 717, following famine and plague in the area.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historia_Brittonum

The latest coins, dating to 388-402, were found in the robber trench of the north portico colonnade…

…

The artefactual analysis of the site (see chapter 6) shows that the inhabitants of post-Roman Wroxeter either continued to use Roman artefacts with little modification other than occasional repair, or were using artefacts made from perishable materials as replacements.In artefactual terms, they are invisible.

….

Discussion of the fate of Roman towns in the post-Roman period has in recent years tended to come to the conclusion that towns ceased to exist soon after AD 400 (Brooks 1986, 1988; Esmonde Cleary 1989, 144-54).The Baths Basilica Wroxeter Excavations: 1966-90

Corbishley, M., Bird, H., Barker, P., White, R., Pretty, K.

English Heritage (1997)

http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/eh_monographs_2014/contents.cfm?mono=1089053

Fifthly: Confusion about how Viroconium was simultaneously two separate cities [with very different names].

The city has been variously identified with the Cair Urnarc and Cair Guricon which appeared in the 9th-century History of the Britons’s list of the 28 cities of Britain.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wroxeter

The History of the Britons (Latin: Historia Brittonum) is a purported history of the indigenous British (Brittonic) people that was written around 828 and survives in numerous recensions that date from after the 11th century.

…

The Historia Brittonum describes the supposed settlement of Britain by Trojan expatriates and states that Britain took its name after Brutus, a descendant of Aeneas.The work was the “single most important source used by Geoffrey of Monmouth in creating his Historia Regum Britanniae“ and via the enormous popularity of the latter work, this version of the earlier history of Britain, including the Trojan origin tradition, would be incorporated into subsequent chronicles for the long-running history of the land, for example the Middle English Brut of England, also known as The Chronicles of England.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historia_Brittonum

Historia Regum Britanniae (English: The History of the Kings of Britain) is a pseudohistorical account of British history, written around 1136 by Geoffrey of Monmouth.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historia_Regum_Britanniae

But, “ the footsteps of several towns and forts, that flourished in the time of the Romans are now so obscure and undiscernible, that we are not to wonder if the conjectures of learned and judicious men about their situation prove sometimes erroneous.”

(Ibid, Caermardinshire, p. 686).These are reasons, which, I trust will be admitted as justifiable for retaining the original names.

Historia Brittonum [with English facsimile] – Rev W Gunn – 1813

https://archive.org/details/historiabritton00nenngoog

Unsurprisingly, the mainstream confusion doesn’t stop here…

Pingback: The Wroxeter Chronicles: Legions, Lead and Lunacy | MalagaBay

I wrote a paper a couple of years ago on the lost rights of way in Wroxeter. It went to the local county council but sunk without trace. It’s a scandal the way local landowners have taken these and made them into their own private roads. The once that particularly incensed me was the one down to the original crossing point on the river Severn from opposite the church. This has been a right of way since roman times but is now someone’s private drive to their house! I’m happy to forward it to anyone who’s interested.

Wroxeter Roman City has a magic all its own. I certainly felt it while I participated in the excavations of the Macellum under Dr. Graham Webster, 1981-1984. And, yes, all these years later, it continues to fascinate.